New Zealand (NZ) is ideally situated in the Pacific Ocean, it is home to 5.12 million people with a population density of 20 people per square kilometer. It is a land of glorious green forests, soaring mountains and sandy beaches, a land made famous by Peter Jackson’s Hobbit movies. However this beautiful country is not immune to the international trends of increased mental health distress. Mental Health distress rates have been increasing for some time, with the rate of increase escalating over the past decade. This increase seems particularly evident in youth and young adults, the easons for which are multiple and complex, although the impact of the COVID pandemic and resulting lockdowns seems to have differentially affected youth.

Looking to available data in NZ, our last formal mental health epidemiology survey (Te Rau Hinengaro – https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/te-rau-hinengaro-new-zealand-mental-health-survey ) showed annual prevalence rates for any mental health or addiction issue of 20% – with the highest rates by age group in 16-24 yo at 33%. The combination of highest prevalence along with greatest opportunity for prevention and early intervention in youth, has meant that since that time this age group have been designated by the Government as a “priority population” for mental health funding and service development.

The national “Youth 2000” survey (https://www.youth19.ac.nz/ ) has periodically surveyed youth wellbeing since 2001, and showed relative stability in numbers of youth experiencing distress and mental health and addiction issues from 2001 to 2012, but large increases from 2012 to 2019. Over this time numbers experiencing significant symptoms of depression almost doubled from 12% to 23%, with significant increases also in numbers experiencing significant anxiety, and suicide thoughts and attempts. Differentially Māori (NZ indigenous population) youth have the highest rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts and behaviour.

This survey shows that youth take advantage of GP care and school health services when they are strugging, however those who are more afluent are most likely to access help. There are significant barriers which combined significantly reduce access for those from lower socioeconomic communities, particularly Māori and Pacific –the polulation with the greatest need.

There has been increased investment in services for youth more recently, although this comes from a historic low base and there remains a sigificant need-capacity gap (in part funding, in part workforce shortages), with waits of months to be seen by secondary Child and Adolescent Mental Health and Addiction (MH&A) services across the country. The rollout of the “Access and Choice” primary and community programmes funded in the NZ Government May 2019 “Wellbeing Budget” (https://www.wellbeingsupport.health.nz/ ) has gone some way to addressing this, via the dedicated Youth and GP based services, but anecdotal reports from GPs, and repeated media profiles, highlight that there remains significant unmet need in this age group.

Further, access for youth to the Access and Choice GP based “Integrated Primary Mental Health and Addiction” service is lower than for other age groups (in the Auckland region, 4.3% annual access compared with 6.4% whole population access) despite this age group having the highest need. Co-design work undertaken with youth from a low socio-economic community, to identify barriers to going to the GP, highlights that GP clinics are seen as an “adult” space that they would not attend unless parents took them, or they had acute or sexual health need so had no other option. They would not attend their GP for a mental health problem.

Whakarongorau, the integrated suite of NZ National Telehealth Services (https://whakarongorau.nz/ ), includes the 1737 “Need to Talk” multichannel 24 hour free counselling service, established in 2017 (previously all mental health and addiction telehealth services had been phone only). The service has been widely promoted to the population, in particular through the time of the Christchurch Terror Attack (March 2019), and the periods of COVID lockdowns, resulting in significant increase in contact volumes over the past 5 years. The most utlisied method of connecting for youth is disproportionately via text.

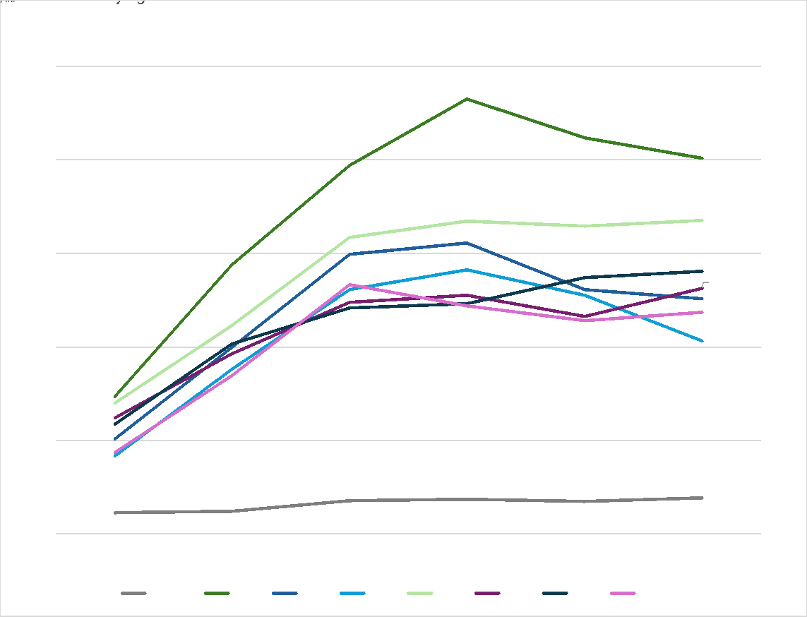

Since it’s inception in 2017, 1737 volumes grew slowly as the service was socialised to the public, and by 2018 it was widely recognised. If we look at volumes since 2018, overall volumes of contacts have increased by 145%, but differentially by far the biggest increase has been among youth with increase of 174% in 13-18 yo access rates.

So it seems, given the choice, youth needing support with their mental wellbeing in NZ at least, increasingly reach out to telehealth delivered services for support. Anecdotal evidence (comments made in the service “net promotor score” survey; content from past quality improvement focussed service user co-design sessions) suggest that youth value the anonymity (identity can be with-held if the person wishes), immediacy 24/7, and ability to reach out/get support via text, of 1737.

1737 “model of care” is “one-off intervention with an open door to return”, average duration of calls is 15-20 min, and of text exchanges (staff manage up to 5 text exchanges simultaneously) is 45-50 min. On a foundation of traditional counselling skills the counselling team has increasingly been upskilled into use of “focussed Acceptance and Commitment Therapy” (fACT) (Strosahl, K., Robinson, P., & Gustavsson, T. (2012). Brief interventions for radical change: Principles and practice of focused acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications.), a theraputic approach grounded in positive psychology, and ideally suited to a service environment of “one off intervention with an open door to return”. Intent for all but calls relating solely to provision of information, is to end the exchange with the person having a plan of action, and sign-posting to other available services is a frequent outcome in particular for those with more complex need. While we have no way of knowing how many of those sign-posted to other services actually access those services, experience in other settings (eg Emergency Departments) suggest very few follow through on this advice. In an ideal world referral to those services would be enabled; currently that is not possible for a national service. Significant risk is addressed via warm transfer to mental health crisis services, or activating emegency services; where risk is serious but consent not forthcoming, this is achieved via a “break glass” protocol.

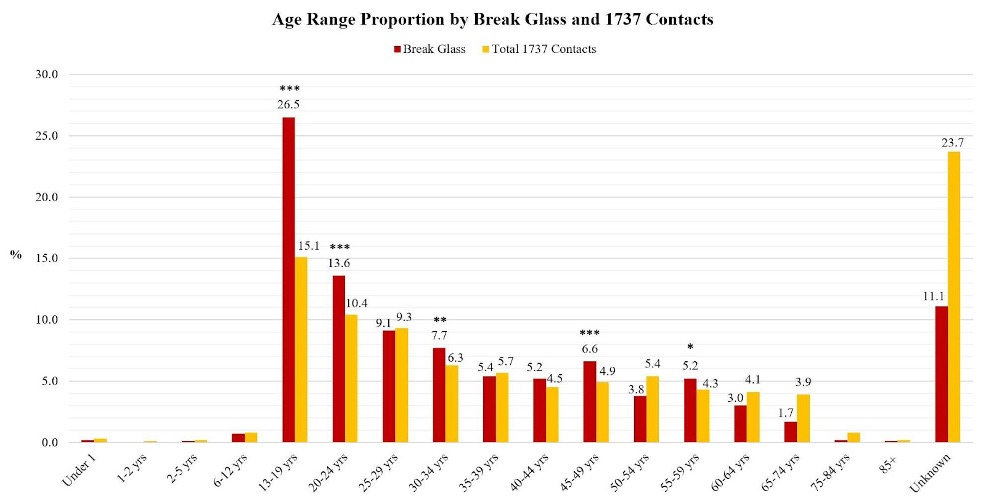

In keeping with historic profiles of those reaching out to helplines, the service pricing, counselling team staff makeup (including a mix of students on a path to a MH&A credential, through to registered counsellors) and model of care is based on meeting the needs of those with “mild to moderate distress”. However in part as a result of the wide promotion of the service to the population, in part due to many/most other mental health services including the specialist sector now routinely including the 1737 number of their cards as their “backup service”, and possibly for other reasons, the level of complexity and risk of those reaching out for support has increased year upon year. More than 40% of those reaching out now are known to specialist MH&A services. Again, differentially the greatest increase in risk/complexity has been seen among youth:

Bar chart representing the proportion of Break Glass incidents and total 1737 contacts for each age group. Values under 1% are not shown in the figure to avoid label overcrowding. Levels of significance are represented by an asterisk (*), with *** being the highest level of significance; p<0.001***, then p<0.01* and finally p<0.05*

In the face of this increase in numbers, complexity and risk of youth reaching out for support, the 1737 team increasingly feel that as a stand alone service what they deliver is no longer “fit for purpose”. This begs the question “what would a fit for purpose digital MH&A service to meet the needs of youth look like?”.

In considering this question, 3 areas of focus seem relevant –

- What would an ideal continuum of telehealth delivered MH&A services for youth look like?

- How can the plethora of evidence based MH&A e-therapy tools and apps be leveraged to achieve greatest reach and impact for youth?

- What role might AI technologies hold in the future of a menu of digital MH&A solutions?

Telehealth Delivered Services:

If youth are increasingly voting with their feet to enter the 1737 “door” to access MH&A support, it is simply a “no brainer” to say we should be able to offer supported access to a menu of other MH&A supports, where this is needed and wanted. For those with need beyond that which “one off intervention with an open door to return” can readily meet, options would include:

- The 1737 phone service offers the option of speaking to a counsellor or a trained peer support worker. Many youth differentially prefer talking to peers than to a professional, and the option of testing on both phone and text lines, offering youth the option of a youth peer support service is intuitively appealing. Facilitating peer support via a moderated social media platform is another option that has been developed for adults but not to our knowledge youth.

- Supported access to telehealth delivered packages of brief talking therapies. Whakarongorau currently delivers this via telehealth, with contracts among other things for many of NZs university health services, to supplement their in person student counselling services. The service – Puawaitanga, Māori for “to blossom, come to fruition” – was designed through a Te Ao Māori (Māori world view) lens, and since it’s inception has reliably delivered engagement rates and outcomes that exceed the average for Māori. Therapy is delivered by a large team of employed and contracted therapists, recruited to reflect the cultural and linguistic diversity of the population served – and includes Māori therapists able to conduct sessions in Māori language. The delivery platform allows people to review the photographs and bio’s of the large team of therapists, select the therapist of their choice, and then access that therapist’s schedule and book a time that suits them. In an ideal world we would wish to be able to pathway any youth presenting with more complex needs to this service.

- As noted above the existing 1737 team are well equipped to respond to mild to moderate need, but not to people presenting significant complexity and risk, where a more highly trained and clinically skilled workforce equivalent to a secondary/specialist mental health service, is required. Redesign of the “model of care” to better meet need would thus require building a second line clinical service into the team, so counsellors always had a clinician colleague to warm hand-off any texts or calls where the risk and complexity exceeded their capability to safely and effectively manage this.

E-therapy tools:

The NZ population has free access to a significant range of mental health and addiction e-therapy tools and apps, including a number specifically developed for youth (https://landing.sparx.org.nz/; https://www.headstrong.org.nz/; https://www.tearaharo.ac.nz/project/whitu/ ). One of the biggest historic issues with impact of these tools has been the very poor rates of completion of e-therapy programmes, and of continued engagement with and use of apps. The much increased focus on “User Experience” has gone some way to addressing this, but the problem remains.

As the “digital natives” in our populations, youth are most open to, and in many instances prefer, using tools such as apps and e-therapy tools. There is some evidence that access to a mix of automated text and person delivered manual-based “coaching” does increase adherence rates. Such coaching is a role that an unskilled and ideally youth/young adult workforce such as students could be readily trained in and delvier as a low-cost way of increasing the impact of these tools.

AI technologies:

As highlighted in prior thought pieces for this publication, as a new technology AI holds great promise to enable many aspects of healthcare including mental health and addictions, but the hype currently exceeds the state of development regarding both capability and safety. However given the predominant use of the text channel by youth reaching out for support, the potential to move to an AI platform text response system, which is human moderated (ie reviewed and amended if needed, prior to being sent), offers significant opportunity to better meet demand within current staff capacity, and with much shorter wait times. Whakarongorau holds a huge database of quality reviewed text exchanges, which could potentially be a basis for training an AI platform in what “good” looks like in responding to people reaching out for help with mental health and addiction chalenges. Previous research has shown that if offered the choice, many people in particular those younger, would choose AI delvered support and therapy over human delivered, suggesting this would be a very acceptable option for youth.

Longer term however, given the realities of both workforce shortages and people’s preferences, the potential to train an AI platform to deliver both phone and text responses autonomously hold enormous promise – with ideally those reaching out being given the choice of human vs AI “counsellor”. Likewise the potential for an AI coach to support greater rates of completion of e-therapy programmes, and ongoing engagement in use of app’s, is significant.

Summary

The number of young people with Mental Health distress is increasing in New Zealand, this is reflected in the volume of texts seen to the free to chat line 1737 provided by Whakarongorau Aotearoa. In order to address the needs of youth we must take advantage of the front door that 1737 provides as a familiar safe place to access care. Leveraging technology in order to do this will be key in a complex environment where needs are great and the workforce is stretched. AI and e-therapy tools could aid in the navigation of services and the provision of ongoing connection and care.

Learn more about Whakarongorau Aotearoa at their website >>